There is a debate in our country about youth tackle football. Boston University has been publishing studies about concussions, and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) for about the last 7-8 years which specifically outline the dangers of football. (Editor’s note: We recently defeated the ban of youth tackle football here in California.)

They admit within the studies themselves that the studies are flawed because most of them are heavily one sided. Meaning that they are studying the brains of former players whose families had already suspected mental issues with the former player. Or, there has been documented issues with those former players.

The science is not clear. Here is an article by a former NFL doctor saying there is no link between CTE and youth tackle football.

Many doctors are in full agreement with that. They just aren’t getting the same media attention because it’s not “click bait.” To say 110 of 111 former NFL players have CTE gets the clicks.

Here is an article submitted on behalf of 26 brain injury experts in neurosurgery, neuropsychology, neurology, neuropathology and public policy at 23 universities and hospitals in the United States and Canada that says the truth is not about banning youth tackle football is not so simple.

I saw a sports doctor tweet out her opinion (see below) about football and brain injuries. It made a whole lot of common sense.

So I reached out to her for an interview.

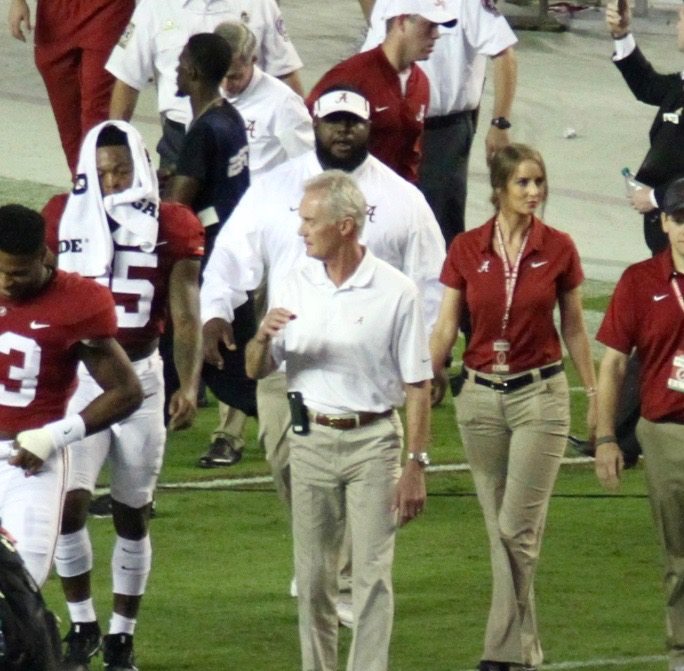

Dr. Aloiya Earl (follow her on Twitter) is completing her residency in Columbus, OH and starting work with the University of Alabama athletics in July as a subspecialist fellow in sports medicine. Obviously, a very well-educated woman working among the top college athletic programs in the Nation.

Thank you for your time Dr. Earl!

What is your own background in sports?

Through high school, I was a distance runner and I played volleyball. Cross country and track were my focus, and I went to the University of South Carolina for these sports. I had so many stress fractures and other injuries from overtraining, so my competitive running career was cut short. I’m grateful, though, since those setbacks propelled me to my current career.

My activity of choice now is weight training. I became a bit disillusioned with running, but I still have nostalgia when working with endurance athletes, and I enjoy being able to relate to them and treat their injuries to aid in meeting their performance goals.

What made you want to become a doctor?

I became fascinated with sports medicine as a career option way back when I was a freshman in high school, through an interest in my own athletic injuries. I began shadowing my sports medicine physician in his office, and immediately had a natural affinity for this field and for the musculoskeletal system. Working to keep athletes and active people well, doing what they love, is tremendously rewarding.

How do you think that public awareness about concussions has changed over the years from your view as a doctor?

I think now more than ever, the general public is more informed about the symptoms of concussions and the risks of returning to sports too soon after a concussion. I think myths have been dispelled; for example, you do not need to have a headache to have a concussion. The media has sensationalized the topic of concussions in recent years, and while I don’t agree with all of the messages the media propagates regarding these injuries, I am happy to see increased education and awareness because of it.

How do we continue to encourage athletes to self report their injuries?

From my experience, the best message to athletes is that the earlier they report symptoms, the quicker they will recover and return to play. Athletes are performance-driven, so our advice to them needs to be tailored as such. It’s also important to reassure them that it’s okay to err on the side of caution when it comes to approaching their trainer or physician. I would rather have 100 athletes over-report symptoms, than to have 1 athlete under-report.

Why do you think football is “in a better place than ever?”

This comes back to the increased public awareness and widespread education about concussion symptoms, risks, and management. Trainers and physicians are not the only members of an athlete’s care team. Parents, coaches, officials, teammates, and athletes themselves are all becoming equipped to recognize concussions, and all these individuals are encouraged to report symptoms. Football has a more comprehensive team of on-field surveillance than ever before.

What do you think about lawmakers wanting to outlaw youth tackle football before a certain age? 14 in some states, 12 in others.

There is minimal research done on the potential long-term effects of tackle football and head trauma in this age group; there is still much work to be done in this area of study. I understand the intent of the policy makers, keeping health and safety as a priority for our youth athletes. While I maintain football is “more safe than ever,” I cannot say football is without risk. I can’t say that for any sport. Women’s soccer, for example, is a very high risk sport for concussions. The exact risks and the extent of their consequences are unknown, and I’m not sure we’ll ever have a perfect answer for this. Regardless, I think these policy changes will at least ease the minds of many parents who worry about their children getting repetitive head trauma and microtrauma from tackle football, and hopefully allow for them to still sign their children up for flag football as an alternative. The benefits of youth sports participation cannot be overstated, so if this change helps keep more children active, I’m supportive.

The studies out of Boston University have painted football and all contact sports in a very bad light. Is that fair to do with the limited information we have about CTE?

I never want to discount any research that’s been done, especially research done with the intentions of keeping athletes well. Sports medicine is a community of professionals who want athletes to perform well and stay healthy, and I support all efforts to foster those common goals. That being said, I do think a lot more work needs to be done in this area of research. I’m interested in the potential confounding variables that may contribute to the emotional and psychological pathology affecting, for example, professional football athletes after retirement. These athletes lived their lives as superstars, and their sport was a key part of their identity. Does the drastic transition from a career as a professional athlete to “life after football” play a role in these pathologies? Anecdotally, my observations support this. This does not discredit CTE as a theoretically clinically-significant entity, but I think more variables need to be explored, and I think the overall picture is complex and multifactorial.

Thank you for sharing some unique insight on this national debate Dr. Earl!

Chris Fore has his Masters degree in Athletic Administration, is a Certified Athletic Administrator and serves as an Adjunct Professor in the M.S. Physical Education – Sports Management program at Azusa Pacific University. He runs Eight Laces Consulting where he specializes in helping coaches nationwide in their job search process. Fore was named to the Hudl Top 100 in 2017, and the Top 5 Best High School Football Coaches to follow on Twitter by MaxPreps in 2016. Follow him!